From Teaching Associate to Award-Winning Teacher, Citizen Schools Alum Jessica Lander finds a Passion in Teaching and Working with Immigrant and Refugee Students

Meet Jessica Lander! Jessica is a former Citizen Schools Teaching Associate (TA), who taught at the Edwards Middle School (Charlestown, MA - closed in 2021) from 2011–2012. Currently, Jessica is an EL History and Civics High School Teacher in Lowell, MA, having taught there starting in 2015. Her impactful work goes beyond the classroom, as she has also authored three books, including her most recent publication, (available for pre-order now) Making Americans: Stories of Historic Struggles, New Ideas, and Inspiration in Immigrant Education (Beacon Press, Oct 4, 2022).

We took some time to catch up with Jessica and hear all about her current work, and how Citizen Schools powerfully impacted her teaching journey.

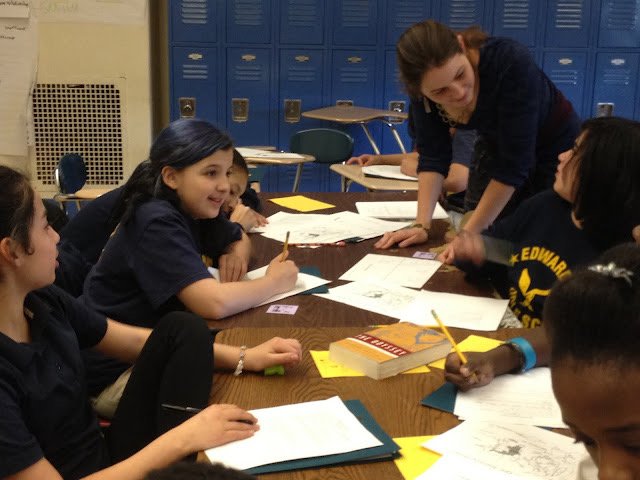

Jessica Lander was a Citizen Schools Teaching Associate at the Edwards Middle School in 2011 and 2012.

Talk a little bit about your role as a TA with Citizen Schools, how did it spark or elevate your involvement with education?

My memories of teaching and learning with 6th graders at the Edwards Middle School in Charlestown (the Eddie, as we called it) leaps into full-color focus, despite the distance of a decade.

Two-minute math challenges my students would race to complete and pencil percussion performances drummed out on the edges of desks amid English lessons. Field trips to a local recycling facility as part of our class’s advocacy to establish a school-wide recycling program, and the afternoons my students fanned out throughout the halls and classrooms to interview classmates for a documentary about being 6th graders. For a semester my students and I dove into Macbeth—penning our own Shakespearean slander and writing text-message renditions of Lady Macbeth persuading her husband to murder King Duncan (Macbeth: Hey Lady! Wutz up? Lady Macbeth: U Cerealz need 2 kill da king).

But I also remember the moments before my students arrived in my classroom each day. Every morning the Citizen Schools teaching team would meet together. We had a small office with a shared table we would crowd around on the second floor of the Eddie. Together we would lesson prep, problem solve, share high points (and low points) from our classes the day before, and review new teaching techniques shared with one another. What stands out to me from my time at Citizen Schools is that we were a team. When I was struggling to teach a concept or best support a student, my colleagues were there to talk through ideas or come into my class and observe. When I bounced in excitement about an elective idea, they were there to eagerly listen. Because I was surrounded by colleagues who cared, and many of whom became good friends, I grew so much more as an educator and as a person.

“For young people, a sense of belonging provides a foundation for building a life and pursuing one’s dreams.”

Give us an overview of your new book. Why is it an important piece for other educators to read?

Since 2015, I have taught recent immigrant and refugee students at Lowell High School. Wanting to learn how to better support them, three years ago (2019), I set forth from my classroom to begin work on Making Americans: Stories of Historic Struggles, New Ideas, and Inspiration in Immigrant Education, (Publication Oct 4th 2022)—to visit innovative schools working to support immigrant-origin students, to delve into the history of our country’s approaches to immigrant education, and to learn from my own students. To reimagine how our country can better educate newcomer children, I believe we will need to understand our past, explore present innovations, and listen to the personal stories of young people themselves. These stories include:

Essential history that has shaped our nation and our schools, including the stories of: the Nebraska teacher arrested for teaching an eleven-year-year-old boy in German who took his case to the Supreme Court; the California families who overturned school segregation for Mexican-American children; and the Texas families who risked deportation to establish the right for undocumented children to attend public school.

Extraordinary educators and school programs working across the country, including: A school in Georgia for refugee girls who had been kept from school by violence, poverty, and natural disaster; five schools in Aurora, Colorado that came together to collaborate with community groups, businesses, a hospital, and families to support newcomer children; and a North Carolina school district of more than 100 schools who rethought how they teach their immigrant-origin students

And my remarkable former students, including: Choori, a boy who escaped Baghdad and found a home in our school’s ROTC program; Srey Neth, the daughter of Cambodian genocide survivors who dreamed of becoming a computer scientist; and Robert, an orphaned boy who escaped violence in The Democratic Republic of the Congo and created a new community here.

I believe we all have so much to learn from this history, these educators, and these young people. Together these powerful stories provide important lessons on how educators and schools can nurture a sense of belonging. We as teachers all have roles to play in guaranteeing that young newcomers come to believe they belong in our classrooms, in our schools, and in our communities. For young people, a sense of belonging provides a foundation for building a life and pursuing one’s dreams. I’m excited to share these powerful stories with all of you.

Jessica and some representatives from her classes in Lowell presented at the Massachusetts State House.

What do you see as the biggest hurdles for immigrant origin students after this past year of teaching? How can we work towards a more equitable system?

For many of our students, and for many of us educators, learning and teaching amid a devastating pandemic has been deeply challenging. On top of trying to learn remotely, many students juggled responsibilities at home, caring for siblings or elderly family members. Many struggled with shaky, unreliable internet and with loneliness. Some grappled with depression. For older students, some made the difficult but necessary choice to devote many hours to jobs to help support their families, logging into online classes from work. As reports have detailed, schools during the pandemic struggled particularly in teaching and nurturing English Learner students.

As we set up classrooms and welcome students back to school this year, I believe we have an opportunity to reset and re-imagine what immigrant education can look like in our lessons, our classrooms, our schools, and our communities.

In researching and writing Making Americans, I had the opportunity to learn from educators, researchers, organizers, policymakers, and young people. I was inspired by the powerful, creative, and innovative work happening right now in classrooms across the country that have created welcoming communities that nurture for students a strong sense of belonging.

But I was also struck by how remarkable teachers and innovative programs were isolated from one another. Far too often, teachers are disconnected—with limited opportunities and time to learn from colleagues in their communities and beyond. I’m reminded about how powerful it was to be part of a team of educators all working together when I taught with Citizen Schools.

Looking forward, my hope is that we can create sustained opportunities that draw educators and others together so that they have an opportunity to learn from and collaborate with each other—working together to share best practices, problem solve, and create new approaches to reimagining immigrant education.

Jessica and her students who wrote We Are America.

What’s one personal accomplishment you’ve made outside of the school day?

From a class project in 2019, my former students and I launched the national We Are America Project, which mentors teachers and works with students to share students’ personal stories of American history and identity. We collaborate with ~70 teachers in more than 25 U.S. states, who work with more than 1500 students—helping the next generation share their histories.

The project traces back to 2018. To understand the complexity of this nation’s history, my students and I believed it was important to make it personal. High school history classes often center on analyzing the actions of nations, the large-scale transformations of communities, and the broad trends in society. Such history is, of course, essential. But, history is also the collection of millions of individual stories and experiences. My students set out to understand how laws and movements intertwined with their families’ histories. They began claiming movements, marches and policies as part of their own histories. And, as they listened to each other’s stories, they learned to empathize with one another. My students wrote and published two books—We Are America, and a sequel, We Are America Too, sharing their voices and stories in our community. Before the year was over, we realized they had struck a chord. Believing the work needed to grow, together, we launched the national We Are America Project. Our goal: to help spark, in classrooms and communities nationwide, a new conversation around what it means to be American.

My former students and I are now working with our fourth cohort of teachers and their students. Each year these classes share their stories in published books in their community and in our website library for everyone to learn from. Through the We Are America Project, my students and I hope, in our small way, to help change that understanding—both for students themselves, but also adults across the country. We hope to help create space for each young person to claim publicly their American identity and their place in our country’s history and our future.

We hope you will consider buying Jessica’s new book Making Americans: Stories of Historic Struggles, New Ideas, and Inspiration in Immigrant Education. You can stay in touch with Jessica’s work by visiting her website or following her on Twitter (@jessica_lander)